Music Education

BLUEGRASS HARMONY VOCALS

Some notes about how to sing bluegass & oldtimey harmony by Rick Townend

| Share page | Visit Us On FB |

BLUEGRASS AND OLD-TIME HARMONY vocals are usually: a lead part (the melody); a tenor (high); plus for trios a baritone (usually just below or above the lead), and for quartets a bass part (right at the bottom). Generally, men's vocal ranges are between G above middle C and the G two octaves below that; of course only a very few men have that whole two octaves - someone with a high range will sing 'tenor' and with a low range will sing bass - lead and baritone somewhere in the middle. Within a group, you are likely to find enough variation; many classic tenor singers (e.g. Bill Monroe, John Duffey) also sang lead - hence the 'high, lonesome sound'.

BLUEGRASS AND OLD-TIME HARMONY vocals are usually: a lead part (the melody); a tenor (high); plus for trios a baritone (usually just below or above the lead), and for quartets a bass part (right at the bottom). Generally, men's vocal ranges are between G above middle C and the G two octaves below that; of course only a very few men have that whole two octaves - someone with a high range will sing 'tenor' and with a low range will sing bass - lead and baritone somewhere in the middle. Within a group, you are likely to find enough variation; many classic tenor singers (e.g. Bill Monroe, John Duffey) also sang lead - hence the 'high, lonesome sound'.

Some general musical background:

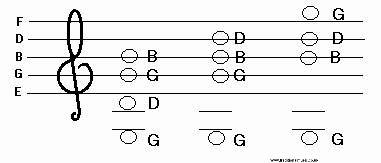

Basic chords are made up of three notes, 1 + 3 + 5 of the scale - doh + mi + soh; for example a C chord is C + E + G, and a G chord is G + B + D.

These three notes may be in any order, and you can have as many of each as you like - for example in a G- chord on the guitar, you have three Gs, two Bs and one D.

For Vocal Harmonies in bluegrass/old time music, generally the lead, tenor and baritone each take one of the three notes of the chord; the bass sings the note of the chord-name, as low as s/he can make it. For example, here are three ways a G chord might be harmonised in this way:

Note: throughout this CD and notes, I'll use the convention of setting all the notes on the treble clef. For male voices, just sing everything one octave lower.

In formal music jargon, the group of the top three notes in each chord above is called a 'Triad': the middle example is called the 'Root Position Triad' (because the G is at the bottom), the last example is called the 'First Inversion' B at the bottom) and the first one is called the 'Second Inversion' (D at the bottom).

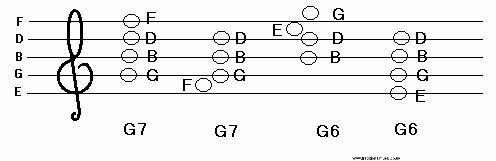

A Seventh Chord (G7, D7 etc|) has the main three notes as above, plus a note which is two semitones (two frets) below the key note of the chord. Technically this is the 'flattened' seventh not of the scale (the actual seventh note of the scale is only one semitone below, or 11 semitones above, the key-note). This sounds complicated, but if you play a seventh chord you can see why this sound is much more useful than the one with the 'true' seventh note of the scale (called a major seventh - "+7"). For example, on the guitar, you can see that a standard G7th changes the G note (3rd fret) on the 1st string for an F (1st fret); if you change that to an F# (2nd fret), you'll have a G+7: try it to see what it sounds like - useful, but only in limited circumstances! 7th chords are extremely common in all kinds of music, particularly as an indication of a chord-change about to come.

Examples: C7 = C + E + G + Bb, G7 = G + B + D + F, D7 = D + F# + A + C,

A7 = A + C# + E + G.

Sixth chords are the three main notes plus the 6th note of the scale: e.g. C6 = C + E + G + A, G6 = G + B + E.

Here's how some G7ths and G6ths look on the musical staff:

As you can see, the notes can be in any order.

Here I'll put in the only absolute rule that really matters:

IF IT SOUNDS RIGHT, IT IS RIGHT!!

The 'rules' of harmony only try to explain why a piece of music sounds right. What I'm giving you here are some guide-lines to help make up a typical bluegrass/old-time harmony vocal sound.

Making harmony parts

An observation: apart from the Lead (the basic tune) don't expect any of the other parts on their own to sound pretty; they'll only sound nice in combination with the lead.

It is quite possible to learn to sing harmonies just by 'having a go'; like many thing in life, do it again if you like what you've done, if not - try something different next time! Gradually you'll get better at doing it. Many of the early classic bluegrass songs are simple to harmonise; songs with a complicated melody and chords are likely to be more difficult. For myself, I've always enjoyed trying to search out the pattern or 'schema' behind things, and it has been fun seeing what the nice harmony sounds have in common; understanding the theoretical side has also been a great help when tackling a difficult piece of harmony.

If you want it to sound good, you will have to spend some time and concentration on harmony - if it doesn't come naturally, it's fine to take each note of the song or chorus separately and work out the parts; you can do this by getting the lead singer to sing and hold the note, then getting the bass (if this is a quartet) to find the keynote of the chord at the bottom, then getting the tenor to find a note, then last of all the baritone. It may help to write out a staff, write down the lead singer's note, and then, using the chord structure principles above, write out all the possible harmony notes for the other parts to choose from.

About each part:

As you can see, the Bass part is easy - you can always just sing the 'name-note' of the chord, as low as you can make it. In a G chord, the bass would usually sing the G an octave below the G below middle C. You can of course sing other notes if you find ones you like. In particular it may sound nice, when about to change chord, to lead into the new chord, like the guitarist when s/he does a run: for example going from G to C, you could sing - G A B | C.

The Lead part may seem obvious - it is the tune - but I'd make one plea to lead singers: please don't change the tune, once you have decided on a version you like! It makes it difficult if not impossible for the harmony singers to make a nice sound for the band if the lead singer doesn't keep to the tune they are expecting.

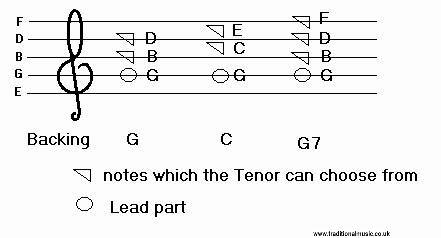

The Tenor part is above the Lead (tune). So a good way of starting is to sing the same note as the lead, and then try singing the notes in the chord above it, and see what you like best. For example. If the backing chord is G, and the lead is singing a G, you can choose from B and D (below, 1). If the backing chord is C and the lead is singing G you can choose from C or E (below, 2). If the backing chord is G7, and the lead is singing G, you can choose from B, D or F (below, 3)

Important note: There is one other factor, special to Bluegrass and Old Time music, especially on the more 'mountain' sound songs. Because these kinds of music are based on an older, modal tradition, it can often sound good to 'pretend' that the harmonies don't change, even though the instruments are changing chord. So that the vocal harmonies will keep on working in G, for example, even when the backing chord has changed to C. So, if you are playing a song in the key of G, but the backing chord changes to C. the tenor can choose from B, C, D or E ! So start developing your musical taste right from the beginning, to help you hone in on the sounds you like best.

The Baritone part is the most difficult of all the parts - you have to find the 'missing' note, which the lead and tenor are not singing. So, if the backing is G, and the lead is singing G and the Tenor is singing B, you'll probably go for the D just below the lead's G. If the lead is singing G and the Tenor is singing D, you go for the B - the one just between them. This means that the baritone part is often hopping all over the place, and really will sound completely unlike a proper tune in its own right. If the notes the tenor has chosen make for a really difficult baritone part, you are allowed to negotiate!

Good luck,

Rick Townend

You may also be interested in other Bluegrass Related Items on this site:

Playing Bluegrass

Bluegrass Harmony Singing - Tutorial Learning Bluegrass Jamming -Tutorial Learning to play the bluegrass instruments by Rick Townend Bluegrass Your Fiddle, Insiders guide and tutorial on Bluegrass Fiddling by Rick Townend A more complete definition of bluegrass and its background