Improvisation Methods for

Traditional Bluegrass Music

Basic Instrumental Techniques For The Bluegrass Instruments

| Share page | Visit Us On FB |

GENERAL - Improvisation

BLUEGRASS MUSIC is not just playing a particular set of notes, but it also involves you the musician in an approach - like jazz - where you can make up what you play as you go along; you don't need to memorise loads of intricate fingering. Because the songs and tunes - especially the traditional ones such as are on this series of albums (the Just The Tune Series) - use quite simple chord patterns, you can build up a 'vocabulary' of phrases which you can use in any tune where there is (for example) a bar, or two bars, of G, A, D etc.. At first, the challenge is to get familiar with a few phrases, and then to practice fitting them in. It is then up to you, and your own musicality, to start choosing which bits to fit in where. You can copy phrases you like that you hear other people play, and make up your own too.

BLUEGRASS MUSIC is not just playing a particular set of notes, but it also involves you the musician in an approach - like jazz - where you can make up what you play as you go along; you don't need to memorise loads of intricate fingering. Because the songs and tunes - especially the traditional ones such as are on this series of albums (the Just The Tune Series) - use quite simple chord patterns, you can build up a 'vocabulary' of phrases which you can use in any tune where there is (for example) a bar, or two bars, of G, A, D etc.. At first, the challenge is to get familiar with a few phrases, and then to practice fitting them in. It is then up to you, and your own musicality, to start choosing which bits to fit in where. You can copy phrases you like that you hear other people play, and make up your own too.

Each instrument has its own repertoire of classic (or cliché) phrases, and some are shared with other instruments. These classic 'licks' are a good way in to improvisation. You can find them in books like 'the Fiddler's fake-book', but I really would recommend that you try and get them for yourself by listening to players you like - try taping a short bit of music and listening to it over and over again till you can sing it to yourself; then try fitting it to your instrument and getting it smooth.

As you get better, you'll be able to play an approximation of a tune, then add decorations which enhance the 'spirit' of the tune - as you see it. Everybody's improvisations and decorations are slightly different, and that's one of the joys of the music. There isn't only one 'right' version.

Scales, Modes and Harmonies

While bluegrass frequently uses the standard major scales and harmonies of western music, the Appalachian tradition it grew from used simpler but often more compelling sounds - tunes just using a pentatonic scale (I II III V and VI of the standard scale - e.g. G A B D and E; tunes such as 'Cotton-eyed Joe' and 'Angeline'), or the mixolydian scale (where the 7th note of the scale is flattened - e.g. in G use F rather than F#). Echoes of this are in bluegrass arrangements of 'Little Maggie', 'Old Joe Clark' and 'June Apple'. It's also a trait of classic 40s and 50s bluegrass music that while the rhythm guitarists very rarely used any minor chords, the lead instruments and voices frequently used the notes of minor scales - overlaying them on the major sound of the backing to great effect; 'Foggy Mountain Breakdown' is the classic example.

When playing or singing harmonies, the lead instruments often behave as if the backing instruments never change chord: there is a tendency to use - as far as possible - only the notes of the key chord. Again, this is an echo of an older style, where songs, ballads and tunes were sung or played against a constant drone rather than a fuller harmonic backing.

Chords - a beginner's guide

What is a 'chord'? - Basic chords consist of three notes: the 1st, 3rd and 5th notes of the major scale - a C chord is C+E+G and a G chord is G+B+D. You can have any number of each note in the chord - e.g. on the guitar a G chord has three Gs, two Bs and one D. Minor chords are the same notes of the minor scale - Gm is G+Bb+D. 6th chords have the 6th note of the scale as well - G6 is G+B+D+E. 7th chords have not the usual 7th note but the note a semi-tone below - called the 'flattened 7th note': G7 is G+B+D+F. This is only complicated to explain - not complicated when you hear it! 9ths, 11ths, 13ths, diminished and augmented chords are unusual in bluegrass or old-time music - get a jazz text-book if you'd like to know more.

In any one key, the usual chords are:

- The key chord itself - in G, this is G

- The chord 5 notes down* - in G, C

- The chord 5 notes up* - in G, D

[* the convention is in music that you start counting with the first note!]

The last of these (D in the key of G) is the most important chord other than the key-chord. It's often made into a 7th (D7) and is sometimes called the 'going-home chord'. Try playing D7 followed by G and you'll hear why. Its formal name in music is the 'dominant' chord (key-chord is the 'tonic' chord); it's also sometimes called the V (Roman numeral 5) chord. If you keep going 5 notes up - G - D - A - E - B - F# - C# - G# - D# - A# - F - C - you get back to G, after going through all the seven 'white' notes and five 'black' notes in the 'chromatic' scale. This is called the 'circle' or cycle' of 5ths, and is an important part of the schema for most kinds of music.

Chord charts are something I've always found very useful. Most bluegrass tunes and songs are 8 or 16 bars long, so you can set out the regular chord pattern in a grid:

Red River Valley 4/4

G |

G |

G |

G |

G |

G |

D7 |

D7 |

G |

G |

C |

C |

G |

D7 |

G |

G |

Each bar represents two main beats (at a sort of walking pace) each followed by a lighter 'off-beat'. For one bar a guitarist will play 'pick-strum-pick-strum (crotchet or � length notes); the double bass will play two notes (on those main beats) and the banjo, fiddle and mandolin will play up to eight notes (quaver or 1/8 length notes).

You'll find that many songs and tunes have similar chord charts. Here is a really simple one, for Cotton-eyed Joe, and also Sally Goodin. Transposed down to G it is also the chart for Cumberland Gap and Katie Hill.

A |

A |

A |

E/a |

(the last bar is half E and half A)

Many of the dance tunes have two parts (usually called the 'A' part and the 'B' part - not referring to the keys they are in!). Each part is often an 8-bar pattern repeated. Here is the Soldier's Joy:

D |

D |

D |

A7 |

x 2 |

D |

D |

D/a7 |

D |

D |

G |

D |

A7 |

x 2 |

G |

G |

D/a7 |

D |

I haven't made up chord charts for the tunes on this CD, but you can make them out for yourself, as the chords are shown on each of the tablature/music files.

Left Handed?

Left-handed builds of all the instruments can be bought - try searching in Google etc. under 'Left-Handed Instruments'. You can also ask an instrument builder to make you a custom model. All the instruments except the banjo can just be strung in reverse, though you'll probably want to make some adjustment to the bridge and possibly the nut. I've even come across a left-handed banjo player who adapted his 'picking-hand' style so as to play a standard strung banjo held 'left-handed'. Some players, including Elizabeth Cotton (author of 'Freight Train') and Jim Rooney play a standard guitar held left-handed and again have adopted a picking style to allow for the bass strings being at the bottom and the higher strings at the top - sounds more logical anyway when you say it like that! Lastly, there are some left-handed players, including ace-fiddler Bob Winquist, who play their instrument in the common 'right-handed' fashion: Bob says why not anyway, as the complicated work is with your left hand. But it would be a good idea to decide what you are going to do fairly early on, as it's difficult to change later.

Social music

You can get a lot of help with learning to play, and have fun at the same time, by finding a friend or friends who will play along with you. It's good for getting to keep in time, for widening your repertoire, and simply for enjoying the music rather than letting practice become a chore. You don't need to be in a formal band - the roots of this music are people sitting around enjoying picking and singing; it doesn't have to be an entertainment, though you may well find that it becomes that anyway.

Love your instrument

Do keep your instrument handy, where you can take it up for a 'quick pick' - while the potatoes are boiling or the computer is collecting emails etc.. Get to know what it does well - the nice noises it makes, the feel of the wood, the keys in which you get the easiest fingering (sometimes beginners find it a good idea to start with a capo up the neck - the frets are smaller there). Give it a set of new strings, or a polish. All of this will make you more relaxed and familiar with your instrument and actually help you to play better.

And finally...

How You Learn

Learning is a funny thing. There are lots of elements - e.g.:

• Remembering a particular tune (this series of CDs is aimed at helping you do this).

• Getting a particular way of playing (e.g. the Scruggs-style banjo rolls) to 'flow'.

• Understanding the basis of something - what education people call a 'schema' - e.g. how chords work, or why the twelfth fret is so important (it gives a note an octave higher).

• Making 'progress' over a period so that you feel after a time that you are in general 'better' at doing it.

What learning a musical instrument is about is, broadly speaking:

• Instrumental technique

• Listening ability

• Experimentation and making your own music

Different people do it in different ways - some are:

• 'Practicing' regularly with your instrument(s)

• Just playing a lot, at home or with other people

• Thinking - sorting out problems in your head, and developing the 'schemas' (the basic regular patterns)

• Listening a lot - recordings and live music

• Humming tunes all the time

• Going to a teacher regularly

• Having 'one-off' sessions with an expert player to sort out problems

THE INSTRUMENTS

Appalachian Dulcimer

Traditional right-hand technique is to strum across all the strings with a light pick, or a quill. Sometimes just strum away from you - just on the main beats; sometimes (where it sounds right for the tune) in both directions.

Traditional left-hand technique is to use a small wooden stick or pencil or just your finger, sliding it up and down and only fretting the melody string (or pair of strings, on dulcimers where the strings are doubled). Players tend to adapt melodies so that they move up or down the scale all the time.

Traditional dulcimers are fretted for just the 'diatonic' straight major scale - no sharps or flats. For a handful of the tunes in this CD series this means that there are a few notes which cannot be played on dulcimers like this, and these notes are marked '+' in the tablature. But some modern dulcimers have necks with one extra fret, so if you have one of these play the fret just above the fret number for notes marked '+'.

Please note that when using the dulcimer tablature the strings are placed in the reverse order - the melody string (which you play the tune on, and which is nearest you as you sit with the instrument in front of you) is shown at the top of the tab staff; this is due to a limitation of the tablature software I'm using!

Many skilled players do fret all the strings, and also pick them individually with their right-hand fingers, so there seem to be no limits as to what you can get out of these beautiful instruments.

Autoharp

Back in the 1920s, Sara Carter, Ernest Stoneman and other players generally played the harp flat on a table in front of them or on their lap, using fingerpicks on index and middle fingers and a thumb pick, playing the parts of the strings which show to the right of the bars (with the autoharp placed so that the bass strings are nearest you). Usually, modern players hold the instrument up to them, a bit like you hold a baby, with arms crossed so that the left hand still presses the bars down and the right hand picks the strings - but on the other - 'triangular'- side of the bars; this gives a rather more mellow sound.

In order to play tunes you don't need to know where each note is, because the notes which sound are separated by 'damped' strings and you will quite quickly get the feel of where the note you want is - just make a stab at the area where it is, sliding the pick over several strings, so that you not only play the tune, but a harmony to it as well. Try 'clutching' or 'pinching' - using thumb and fingers all at the same time for the main beats and then a gentle strum for the in-between or 'off-' beats.

See the section on Chords above about what notes are in each chord. You'll find you can play a scale by using this series of chords:

Notes of scale: |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

key of G |

G | D |

G |

C |

G |

C |

D |

G |

key of C |

C |

G |

C |

F |

C |

F |

G |

C |

key of D |

D |

A |

D |

G |

D |

G |

A |

D |

[chord Nos] |

I |

V |

I |

IV |

I |

IV |

V |

I |

Get to know what keys your harp can play in. You can always make new chord bars - for felts, strings and general autoharp advice see www.ukautoharps.org.uk.

Banjo - Bluegrass

Basic Right-hand technique.

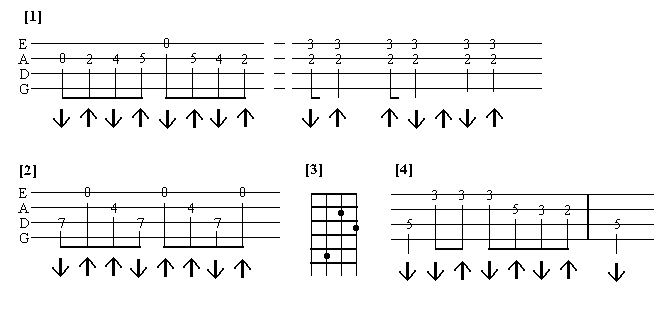

There are lots of ways to get into the bluegrass style; my own is to have fun with the arithmetic - which is basically that you have three fingers with which to play an eight note bar: but threes into eight won't go, so you have to be creative and find a way out! This might be to play two groups of three and then one of two [1 below], or put the group of two in front [2], or combine two bars (16 notes) and play five lots of three and then have a 1-quaver rest [3]. The examples below are in the standard 'G-tuning' - gDGBD:

These examples are all 'index-lead rolls' - they start with your index finger. You can do the same starting with your thumb - or indeed with your middle finger - this is not used very much. Then you can do the same thing backwards [T-M-I] - again not used a lot, as it doesn't seem to flow so naturally for most people. Then there are 'Square Rolls' and 'Forwards and Back' [4 - 7], plus combinations - a familiar 'lick' is [8]:

[nb - H = 'hammer-on' - put a left-hand finger down on the string to make the note;

P = 'pull-off' - take your left-hand finger off the string to make the note. See below under 'frailing']

Other typical bluegrass sounds are 'choking' - particularly the 2nd string at the 10th fret: push it to one side with your left-hand finger as soon as you have picked the string with you right hand finger.

Tunings: The banjo has other tunings which are useful for tunes in C and D. For the C-tuning lower the 4th string from D to C - down one tone. For the D-tuning, lower the 3rd string from G to F# - down a semitone - and the 2nd string from B to A - down a tone. Many players just work with the standard 'G-tuning' for everything (capo-ing where necessary). It's a matter of personal taste.

Melodic style: where a tune is composed of lots of quavers (8th notes) - such as 'Blackberry Blossom' or 'Turkey in the Straw'- standard Scruggs style bluegrass banjo players can only aim at an approximation of the tune; melodic style enables you to play the piece as accurately as the fiddle or mandolin, though you will lose flexibility, and have to learn the piece note for note. Melodic style also makes the most of the limited 'sustain' of the banjo's tonality, by never (unless it's unavoidable) playing two adjacent notes on the same string. For example:

Chords: (when the banjo is tuned gDGBD)

As you can see, the F and D chords have all strings fretted, so they can me moved up the neck wherever you like - e.g. F one fret higher is F#; 2 frets higher is G. I included Eb6 not just for fun, but to show that with a little ingenuity all sorts of unusual chords can be accommodated on the banjo without going all over the neck. If you're interested in chords, rather than buy a book listing them all, why not buy a book - or look on the internet for a site - about music theory: when you know how chords are made up, you can invent your own whenever you need them.

Banjo - Frailed

Basic right-hand technique is:

1. 'pick' a string (any one from 1st to 4th) playing it downwards with your finger nail

2 'strum across the strings - perhaps 1st to 3rd - also downwards, with the same finger-nail or others and then, with your thumb, play the 5th string

in this rhythm (dum-diddy):

1 2 3 4

pick strum - thumb

The 'pick' and 'strum' are in the same rhythm and time as the 'pick' and 'strum' that a rhythm guitarist makes. This 'Pick + Strum' equals half-a-bar when the music is written out or in tablature.

Old-time banjo players all seem to have slightly different ways of making this sound with their right hand, so don't worry if your right hand doesn't look quite like anyone else's; if you're making the sound, you're doing fine. It's not easy to start with! Some banjo players (such as Pete Seeger) pick the first note upwards - it may feel a bit easier, and it sounds a bit different. Doc Watson plays both the 'pick' and the 'strum' upwards.

'Drop-thumb' - with a bit of practice you can fill in the '2' note gap above, by reaching your thumb down and playing a note on the 2nd, 3rd or 4th strings. It's quite difficult; you don't need to do this to play professionally - plenty of the classic old-time banjo players didn't do it. You can also fill in the gap with:

'hammer-ons' - when you've 'picked' an open string, put a left hand finger down (say at 2 frets) and this will make an extra note

'pull-offs' - when you've 'picked' a string which is fretted (say at 2 frets) with a left hand finger, take that finger off, slightly plucking the string with that left hand finger, and this will also make an extra note

'slides' - when you've 'picked' a string which is fretted (say at 2 frets) slide your left hand finger up say another 2 frets, and again make an extra note.

Filling in the '2' note like this gives you 4 notes per half-bar, which equals 8 notes per bar - same as a bluegrass player.

Examples:

Double Thumbing

You can also play tunes leading with your thumb:

Tunings: many old-time banjo players use several tunings as well as the standard G, C and D tunings (see 'Bluegrass Banjo' above). Try these and see if you like the sounds they make:

'Mountain Minor': gDGCD - tunes like 'Cluck Old Hen' and 'Shady Grove' (usually played in A, to make it easy for the fiddle players - you'd put the capo on at 2-frets)

'Double-C' or 'Sawmill': gCGCD - most 'D' tunes (like Mississippi Sawyer) - put the capo on at 2 frets again

'Open C': gCGCE - try this for Angeline (again capo at 2 frets if you play with fiddlers

'Graveyard': g#DGBD - Doc Boggs used this for songs in E (play the E-chord on strings 1-4 - see chords above - and try out the various 'hammer-ons', pull offs and slide possibilities that this gives)

Banjo - Tenor

This instrument was used by some old-time players - the first recorded version of 'Duelling Banjos' was between a tenor and a 5-string - and there is no reason why it shouldn't become a bluegrass instrument in the future (probably someone like Tony Trishka will 'discover' its potential) so I've included tablature. Please note that the tab shown is for the 'standard' tuning of CGDA, not the Irish tuning: if you use the Irish tuning you can get the tunes by looking at the mandolin tab.

Technique is very similar to mandolin - picking down and up. However, if you watch Irish players, they often use triplets for extra excitement, and also they are not so 'fussy' about which direction they pick: if you play a lot in 6/8 time some of the strong notes must be picked upwards. So, have some fun and develop your own style.

Dobro

Buck 'Uncle Josh' Graves made this a bluegrass instrument when he started playing with Earl Scruggs and Lester Flatt in the 1950s; nowadays players like Jerry Douglas and Mike Auldridge have gone on and got some wonderful music of their own from the dobro.

Basic tuning is GBDGBD; you can have fun with other tunings - anything that's a chord in itself will do: e.g. F#ADF#AD. You might like to experiment with ACDF#BD (or one tone lower at GBbCEAC, if your strings are heavy gauge) - this is a tuning used by Sol Hoopii, one of the top Hawaiian guitarists of the 1920s, who is well worth a listen.

Dobro capos are a bit different; if your local music shop doesn't have one try looking at www.shubb.com. There are many kinds of steel bar to try out, have a look at what other people use too. Re picks, most people use a plastic thumb-pick and two metal finger picks (for index and middle fingers) - you could experiment though. Dobro repairs are a skilled job - the resonator itself (under the metal cover) is in tension and could collapse, so have a look on the web, or in a magazine (e.g. British Bluegrass News) for someone with experience.

Hold the bar with some of your left hand fingers touching the strings behind it, to avoid sounds that you don't want. On the dobro it's usual to use all of the neck, not just the few frets at the far end, so get familiar with the important places: in G tuning the 5th fret gives you a C-chord, the 7th fret a D-chord and the 12th (octave) another G-chord; then the 17th fret gives you another C-chord. If you learn these positions you can work from them - e.g. A will be two frets higher than G, E two frets higher than D etc. When playing tunes that go up the scale you can 'hammer-on' (see the banjo section) using the bar (near the end, just on the one string). Dobro players often simplify tunes, or change them to include sounds that the dobro makes really well, so if you find part of a tune difficult, see if you can substitute something you can play that has the same chords as that bit. The dobro also does back-up really well - try listening to some players and recordings you like and start copying. Please remember not to drown out the singer, but to add tastefully in the gaps in the singing.

Special techniques - have some fun with these:

• Hold the bar with your left thumb, index and middle fingers across the strings, say at the 12th fret, and have your left ring finger just touching the second string (behind the bar); pick the top three strings with your right hand, and then 'bend' that 2nd string with your left ring finger, and let it go again - Wow!

• Harmonics - 1: with your left hand just lightly touch any or all of the strings right over the 12th fret, and pick them with your right hand. It makes this special sound because you are dividing the string exactly in two and both halves are resonating. You can also do this over the 7th and 5th frets (dividing the string into 3 and 4).

• Harmonics - 2: hold the bar over the second fret, lightly touch the first string with your right ring-finger over the 14th fret and pick the string with your thumb-pick. Again, you're dividing the string in half, so you get that 'chime' sound, but this time you can move the bar - and the chime moves too!

• Barking (for 'Salty Dog' etc.): with the bar across all of the strings, strum them all across with your right thumb, quickly move the bar up the neck a little, and then suddenly take it off.

Double-bass

In bluegrass and old-time music the bass need only be simple - often the bass player has another important part to play, as lead singer perhaps, or comedian. The basic pattern is 'Root & 5th' on the strong beats of the bar.

'Root' is the key-note of the chord - in the key of G, it's a G note

'5th' is the note 5 up from the key note - in the key of G, it's a D note

You can also play the D below the G - it's still called the '5th', because of its relationship to the G.

For the common bluegrass chords, here are the 'Root & 5th' notes:

Key |

Root |

5th |

C |

C |

G |

D |

D |

A |

E |

E |

B |

F |

F |

C |

G |

G |

D |

A |

A |

E |

B |

B |

F# |

Some old-timers used to play Root & 3rd - the '3rd' in G is a B, in D is an F#, etc..

Upright bass or bass-guitar? I'm much less fussy about this than I used to be, since I played in a band with bass guitar, and found from experience that when the tone and volume settings are right and the player knows the music style, it's very difficult to tell unless you are looking, which instrument is being played. The double bass looks good and traditional on stage, but the bass guitar takes less room and is easier to transport. Or you could try one of the new acoustic bass guitars. If you like 'new-grass' you'll probably want the sound of the electric bass. As a matter of interest, all these instruments are tuned the same - at it's the same as the lower four strings on a guitar, so if you are a guitarist and would like to try playing bass, you can experiment by just using those strings.

Markers for left-hand positions on the neck: If you are learning, you'll almost certainly need to mark (with a paper sticker for instance) a few important positions - at the equivalent of 2-frets and 5-frets for example. This will give you A and C on the first (thinnest) string. Some players actually have pearl markers put into the neck, like on the guitar. Probably as you get more experienced you'll start naturally looking less at the neck, and placing your fingers by feel, so when the stickers drop off you will not need to replace them.

Right-hand: you can get a variety of sound from the bass by plucking the strings near the bridge or away from it. Usually you rest your right thumb on the black finger board to steady it while you use your index and/or middle fingers to pluck the strings. You can also use your whole hand - see 'slapping' below. While you are learning, you'll almost certainly get blisters - you can relieve the pain with sticking plaster or a fingerstall, but eventually the skin will toughen up. You could try nylon strings, which also sound quite good for bluegrass.

Running bass: many bluegrass players nowadays specify that they want the bass only to play 'root and 5th', but back in the 1960s George Shuffler, and also Tom Grey (of the Country Gentlemen) played some really nice fast running bass, both as breaks and as backing. Have a listen to them and see if you like the sound. The basis is that you run up and down the scale, or the arpeggio (the notes of the chord at the moment in time that you are playing), playing four notes per bar instead of the usual two. However, it usually sounds best if the first note in the bar is a root note (i.e. in G it is a G somewhere on the bass) and the 3rd note - the other strong beat - is any note from the chord the guitarist is playing - e.g. in G, a B or a D, or in D7 a D, F#, A or C.

Slapping: even if you only play root and 5th, you can get some extra fun and rhythmic excitement from slapping the bass - pick the strings by laying your whole right hand across them and sort of catching the string you want with the tips of your fingers, then as you pluck the string, lift your hand right off, and on the off-beat bring it quite hard down on to the strings again with a 'slap' ready to pluck the next string on the main beat. You can get quite complicated rhythmically, syncopating the slaps, or doubling the up.

I have not included tablature for the double bass - any of the other instrument tabs will give you the chord pattern.

Fiddle

Bluegrass fiddle grew out of the Appalachian tradition - from where it gets the 'high lonesome' wails, blues - the 'blue notes', and jazz and Western Swing - the fast improvisations and 'spicy' notes. Examples of bluegrass style are:

� sliding up to a note

� playing the same note on two strings (an open string, and with your little finger on the string below)

� and playing two strings at once generally ('double-stopping') - sometimes just playing an open string next to the string you are playing the tune on, as long as it fits with the harmony at the time.

Bluegrass fiddlers use lots of bowing patterns for different effects:

� Saw-stroke - change bow direction for every note

� Nashville Shuffle - long bow followed by two short bows

� Georgia Bow - three notes played up with one down: obviously the down-bow must be played 'harder' so that you don't end up at the bottom of the bow all the time; to make a point of this the down-bow is on the off-beat of the music, giving a nice rhythmic effect.

� Orange Blossom Special shuffle - like the banjo, this is a syncopated rhythm to give a really exciting feel to this 'train-tune'. Each quaver note can be played with a separate bow or some run together for extra rhythmic madness. This kind of shuffle is used in other tunes and breaks too.

As you get more experienced and confident, you'll find that you develop your own bowing style, running notes together as seems right on the occasion, to suit your music.

I wrote a series of articles 'Bluegrass your Fiddle' for British Bluegrass News magazine, and some of these are on their website www.BritishBluegrass.co.uk in the magazine section.

You notice that there are no tablature files for fiddle on this CD - all the other instrument tablatures contain standard notation for the tunes anyway, so use any of them. The mandolin is tuned just like the fiddle, so this may help if you are happy to translate fret numbers to the fiddle neck.

Mandolin

Bluegrass mandolin is an exciting combination of rhythm and melody - more 'traditional' players, copying Bill Monroe's own style, tend to like syncopated rhythms while the more 'modern' players (for example Adam Steffey and Jimmy Gaudreau) go for melodic interest. When not taking breaks the mandolin often emphasises the off-beat with a cut-off 'chop' chord.

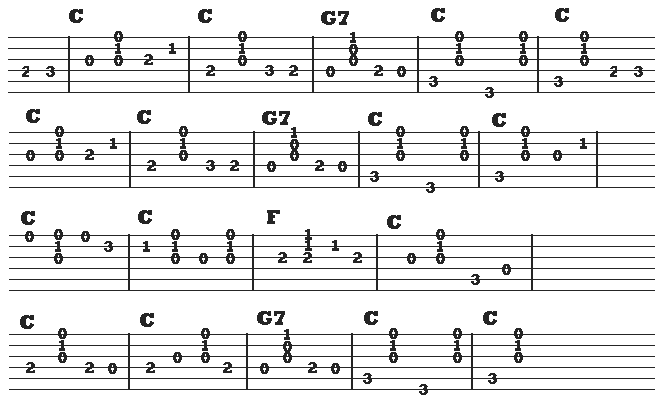

One of the basics is that the right hand always picks downwards on the quaver-notes 1,3,5and 7 of a bar and upwards on notes 2,4,6 and 8 [example 1 below]. However there is a style invented by Jesse McReynolds, known as 'cross-picking' which imitates bluegrass banjo syncopation [see 2 below]; Jesse McReynolds and most other players pick this style as shown - 'down-up-up' - but other players still stick to regular 'down-up-down-up'.

[3] below shows the standard chord shape - this is for 'G', but you can move it around to get other chords - up two frets for A, across to the bottom three strings for C etc.. You only play the strings you are actually fretting with your left hand. A lot of classic bluegrass mandolin licks are based around this shape - for instance [4].

Most bluegrass mandolin decoration is, as for the fiddle, filling out the spaces in the tune - try runs up and down the scale or up and down the arpeggio (the notes of the backing chord at the time you are playing); you can be as creative as you like.

Tremolo - useful for slow tunes, and occasionally for fast ones too. It does take practice: I have found it really helped to try and relax my right wrist as much as possible. You don't have to keep to the rhythm of the piece - in fact it's rather nice if the tremolo is 'against' the time of the other instruments. Try it first on just one string, then on two. You may even want sometimes to use even three or four strings for special effects.

Guitar

The basic bluegrass back-up style is 'pick-strum-pick-strum' - picking the 'root and 5th' notes of the chord on the on-beat (like the double bass) and strumming the top three or four strings on the off-beat. It's well worth getting to know what those root and 5th notes are for each of the chords - for instance in G, the G played on the bottom string (3rd fret) is the 'root' and the D of the open 4th string is the '5th'. In D the 4th string (open) is the 'root' (D) and the 5th string (open) is the '5th' (A). See the general section at the top about chords.

Maybelle Carter played lead guitar breaks mostly based around a C-chord; you can play a scale in C without moving your hand much:

C - 5th string 3rd fret

D - 4th open

E - 4th 2nd fret

F - 4th 3rd fret

G - 3rd open

A - 3rd 2nd fret

B - 2nd open

C - 2nd 1st fret

You can also go down from that bottom C - try it on your own!

A classic tune to start on is the Wildwood Flower:

It's unusual in that the 1st, 2nd and 4th lines all have five bars each, but it's such a well-known tune in this style.

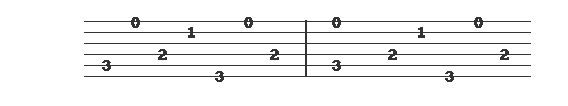

Maybelle and also lots of other guitarists also picked breaks 'finger-style'. Usually you keep a bass line going with your right thumb on the bottom strings, and begin by playing notes on the top strings with your index and/or middle fingers in the gaps between the thumb, and sometimes at the same time as the thumb:

If you like this idea there is a great hand-book by Doug Turner and Rod Davis available from www.scorpweb.co.uk.

Doc Watson was the first lead guitar player really to start playing it like a mandolin - eight quaver-length notes each bar, played down-up-down-up etc. all the time (see the mandolin section). In the 1960s the Stanley Bros used Bill Napier and the George Shuffler on lead guitar - rather similar. They also used cross-picking (like Jesse McReynolds on the mandolin), but played 'down-down-up down-down-up down-up' on the three consecutive strings. However, other players (like Larry Sparks) play 'down-up-up' like Jesse, and still others play down-up-down-up' - standard picking, but over three strings to get the same cross-picking sound.

Capo-ing: outside the bluegrass and old-time world(s) a lot of players are sniffy about people who use capos, but if you look at some of the top players such as Dan Crary and Doc Watson, they use a capo if they need to get the sound that you can only get by playing (for example) in G or C, but their voice needs the song to be in A or D. Some players really develop their feeling for a particular chord-shape, and so use the capo a lot. Or you can decide to have some fun exploring the possibilities of D, E, F etc. Even some jazz guitarists - such as Django Reinhardt - while they didn't use a capo, still would prefer to play a tune in a particular key, so as to get harmonics or particular open string combinations.

Beginnings and Endings

Almost all these tunes begin and end in a traditional way - just something to set the pace, and then a little 'shave and a hair-cut' phrase to bring it to a close. Here are ideas for some instruments:

Fiddle:

Bluegrass Banjo:

Mandolin:

Guitar: