All about the famous song, My Grandfathers Clock

Words and music by Henry Clay Work.

With Sheet Music Score and lyrics arranged for voice and piano also a simplified version with chords and banjo tab, and with the authors little known Sequel song.

| Share page | Visit Us On FB |

MY GRANDFATHER'S CLOCK must be one of the most famous songs ever. It was written in 1876 and embodied enough features, much loved by the Victorians and very much in keeping with the feeling of the age, to make it an instant hit. The story is wonderfully told in lyrics that have a poignant sentimentality as well as supernatural content that fitted well with the romanticism permeating sections of art, literature and music at that time. Most assumed it to be nothing more than a fanciful song, however, the clock this song immortalised is very likely real, and the story it tells is may have at least some element of truth.

MY GRANDFATHER'S CLOCK must be one of the most famous songs ever. It was written in 1876 and embodied enough features, much loved by the Victorians and very much in keeping with the feeling of the age, to make it an instant hit. The story is wonderfully told in lyrics that have a poignant sentimentality as well as supernatural content that fitted well with the romanticism permeating sections of art, literature and music at that time. Most assumed it to be nothing more than a fanciful song, however, the clock this song immortalised is very likely real, and the story it tells is may have at least some element of truth.

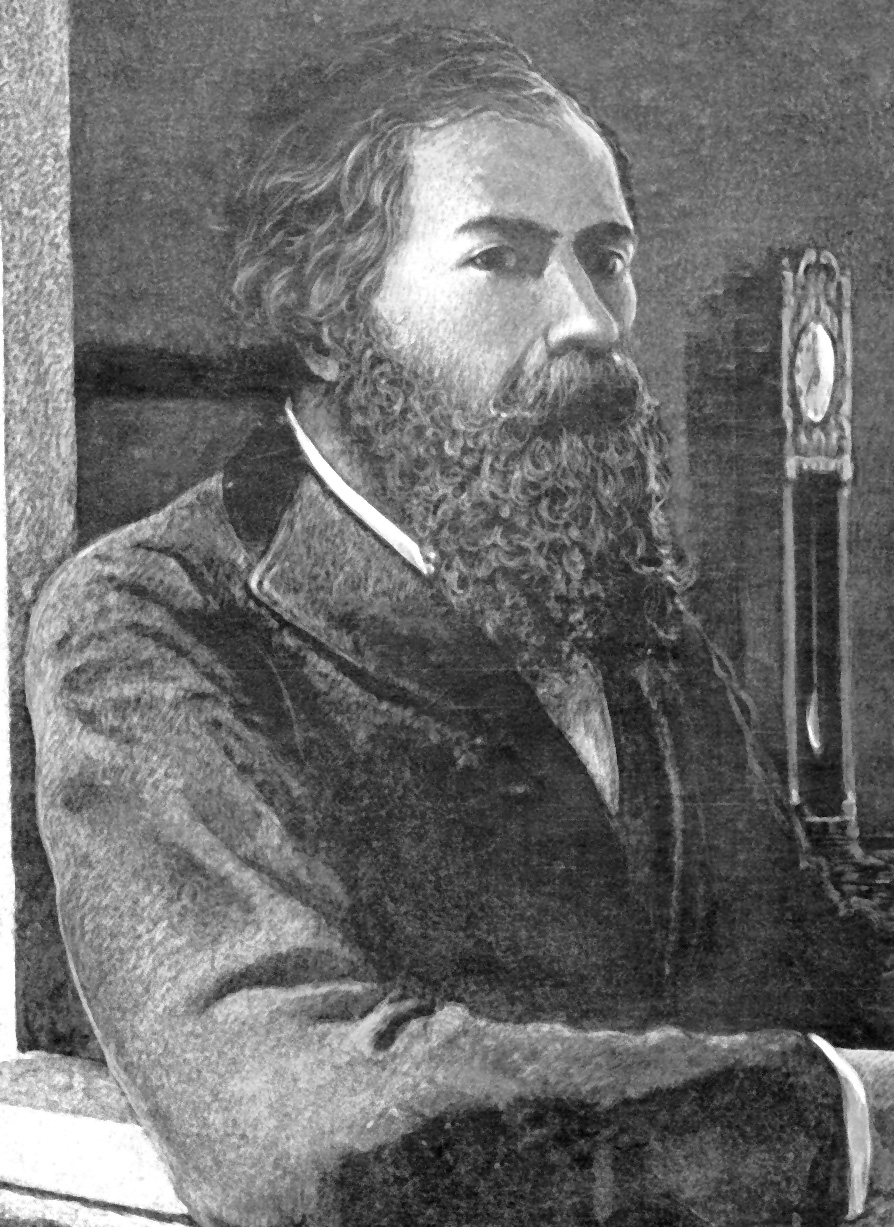

Henry Clay Work |

The George Hotel |

The story began at the George Hotel, a charming 16th century riverside Coaching Inn, in Piercebridge, near Darlington, on the Durham side of the River Tees. It has reputedly had many famous and infamous guests including Queen Victoria’s Prince Consort, Prince Albert, and the infamous highwayman, Dick Turpin. Some of the furniture and outside signage were hand-carved by the legendary Robert Mousey Thompson (1876-1955), also known as "the Mouseman" because of the trademark he created: a small mouse carved on almost every piece of furniture that he or his fellow craftsmen ever made.

About 150 years ago the hotel was managed by two bachelor brothers named Jenkins, and in a corner of the reception area stood a long-case clock, or floor clock, as they were called then. Today, the name of the clock maker - Thompson, of Darlington, is still visible. James Thompson of High Row died in 1825, to be followed by his son Samuel, which makes this clock perhaps two centuries old. Thompson was well known throughout the region for the quality of his watches and clocks, so it is likely that the proprietor of the George Hotel purchased the floor-standing clock from him.

Floor clocks of 6 to 7½ foot tall were quite popular as they allowed the use of long 36” pendulums which gave greater accuracy than smaller pendulums. The floor clock in the George Hotel was reputedly such a good time keeper that and people in town commonly remarked upon it, that is, until one of the Jenkins brothers died, and suddenly the old clock began running slow.

At first it lost a few minutes, then up to 15 minutes per day, several clocksmiths tried to repair it but it ended up losing more than an hour a day. The clock’s problem became as much a topic of conversation as its precision had once been. Then, when the surviving Jenkins brother died at the age of 90, although fully wound, the old clock stopped, according to the stories, at precisely 11:05 and never ran again. The new manager of the hotel tried to have it repaired, but to no avail. So, he left it standing in a sunlit corner of the lobby – dusted and polished, but silent, its hands resting in the position they assumed the moment the last brother died. The inn staff frequently regaled guests with this wonderful story.

And this is where a young American songwriter named Henry Work came into the picture. Henry Clay Work was born in Middletown, Connecticut, on October 1, 1832. His father, Alanson Work, was a noted abolitionist who helped thousands of slaves escape to the north and was sentenced to twelve years' imprisonment in Missouri in 1841. Pardoned in 1845, and destitute, Alanson moved his family back to Connecticut, where young Henry was apprenticed to a printer. Working in the print shop, he picked type out of a case, one letter at a time, which was boring, so he made up ditties and lyrics for songs to suit the clicking sound of placing the type, and employed his leisure in studying harmony. His lyrics were carefully crafted, and the musical setting was of a high standard. He was capable of projecting broad humour (Now, Moses!) or the desperation of a child with a dying brother whose father will not leave the tavern (Come Home, Father!). Most of all, his songs were morally invigorating. His only equals as composers of songs in the Civil War period were Stephen Foster and George Frederick Root (composer of The Battle Cry of Freedom).

Work published his first song, We Are Coming, Sister Mary, in 1853, and continued writing songs while supporting himself as a printer; but, in 1862, he had two breakthrough hits: Grafted Into the Army, in which a "lone widder" bewailed the enforced enlistment of her son, and Kingdome Coming, about emancipating the slaves. With encouragement from George Root, he abandoned printing to make a living writing songs, and came forth with Uncle Joe's 'Hail, Columbia!' (1862), Babylon Is Fallen (1863) and Wake Nicodemus (1864). He became best known, renowned in fact, for Marching Through Georgia (1865), a celebration of General William Sherman's March to the Sea. (This is one you may have heard myself or Jim Gowing play at the club occasionally.)

Between 1853 to 1883, Work wrote 75 songs, at first encouraged by the minstrel show creator E.P. Christy, and then under contract to the music publishers Root and Cady. Today, most of Work’s songs are long forgotten, but two have survived.

More than 20 years before the Titanic left port and never returned, Work wrote his last big song, The Ship That Never Returned.

The tune and the chorus are catchy:

"Did she ever return?

She never returned.

Her fate, it is still unlearned.."

The tune was resurrected in the 1920's and adapted for new lyrics in Vernon Dalhart's 1924 recording of The Wreck of the Old 97 for the Victor Talking Machine Company. The lyrics told of engineer Steve Broadie on the Old 97 making her last run near Danville, Virginia, on September 27, 1903, and the record became the first country" hit, launching the fledgling country music recording industry. It remains ever popular among fiddlers and is a Bluegrass standard.

"They found him in the wreck with his hand on the throttle;

he was scalded to death by the steam."

And the last verse retained Henry Work's "never return":

"...never speak harsh words to your true lovin' husband;

He may leave you and never return."

In the 1950's The Ship That Never Returned was converted back to a train song, this time as a Boston subway train in the Kingston Trio's 1959 hit The MTA Song. It was the passenger, Charlie, who never returned; not having another nickel, he couldn’t get off the train and simply continued riding the non-stop subway round and round the system. The chorus echoes Work's original chorus with a change from the high seas to the subterranean rails:

"He may ride forever 'neath the streets of Boston;

He's the man that never returned."

Work’s life took a tragic turn at the end of the war. He had married Sarah Parker in 1857, and they had four children, but his wife went insane in 1865, went to live with relatives, and had to be institutionalized. Returning from Europe in 1865, he invested the fortune that his songs had brought him in a fruit-raising enterprise in Vineland, New Jersey, and it failed. He pursued a younger woman in vain, and died on June 8, 1884, at the age of 51. He was buried beside his wife in the Spring Grove Cemetery in Hartford.

The year he died, his nephew, Bertram G. Work, published 37 of his songs in The Songs of Henry Clay Work (reprinted in 1920 and 1974), and 18 of his songs were included in S. Brainard's Sons' Our National War Songs, among 14 by George Root, two by P.P. Bliss, and several others. Root himself rated Work as the best of the Civil War song-writers, concluding: The melody and verse of Henry Clay Work...reveal more than the national history of the Civil War. They picture, they record the life of America as it was changing from the last pioneer days into the present great industrial era.

Work was staying at the George Hotel while on a trip to England in 1874 when his all-time greatest hit came to him. Told the story of the old clock, and seeing the clock for himself, he composed a song about it, dedicating it to his sister, Lizzie. The song was published in America in 1876 and sold more than one million copies of sheet music. It remains Work’s best-known song, and was recorded by such diverse artists as bandleaders Gene Krupa and Lawrence Welk, folk singer Burl Ives, children’s TV host Captain Kangaroo, and rock foursome Boyz II Men.The type of clocks he memorialized had been called a case clocks, coffin clock, standing clocks, upright clocks, long clocks, pendulum clocks, and floor clocks. But, after publication of Henry Work’s song, they became forever known as Grandfather clocks.

You may also be interested in other Older Popular Music related items on this site:

And some more specialised items

1940s Top Songs, 200+ songs popular during world-war 2, from Vera Lynn, George Formby, Gracie Fields, Glen Miller, the Andrews Sisters etc WW1 Songs, 190 Lyrics for songs from the World War One(WW1) Era(c1900-1925), also with PDF GEORGE FORMBY SONG BOOK,190 songs some with chords and MP3 of original audio recordings, inc PDF NOVELTY SONGS, 300 song lyrics, of popular comedy, parody and one-hit-wonders, with PDF PROTEST SONGS, 380 songs about anti-war, civil-rights, injustice, racism, social exclusion etc. lyrics & chords with pdf THE SKIFFLE SONG BOOK,200+ greats from Lonnie Donegan,The Vipers,Chris Barber, Chas Mcdevitt and other Jug and Skiffle bands