Bluegrass Your Fiddle Part 6

Bluegrass Fiddle Tuition by Rick Townend

| Share page | Visit Us On FB |

Bluegrass your Fiddle Part 6

Bowing

The use of the bow is a large part of what makes bluegrass fiddle so different - and so exciting. Bowing styles have been borrowed from (and in some cases not given back to) Old-Timey, Cajun, Jazz, European folk styles and classical techniques, but the particular use of them to bring out and develop the nature of bluegrass music is what I'll try to talk about here.

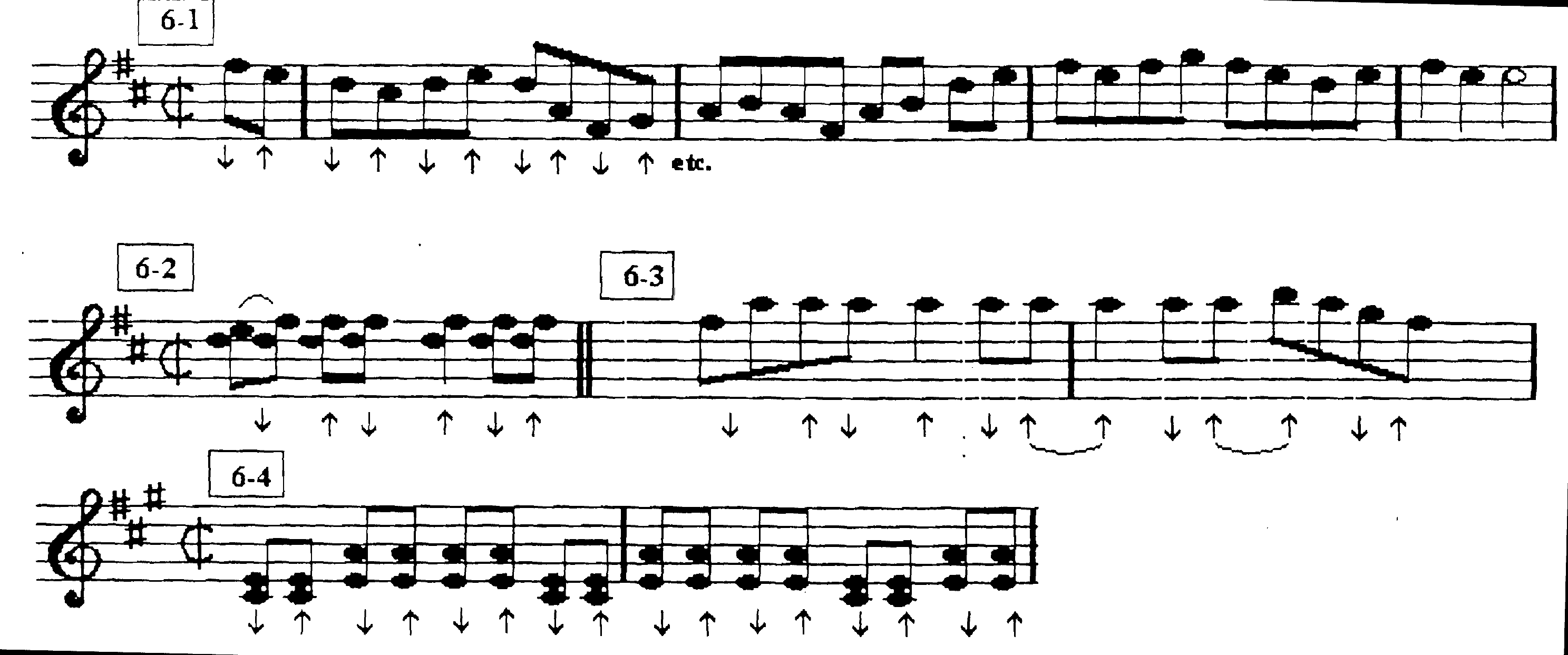

“Saw stroke” refers to the straight alternate up and down bowing for a standard dance tune, largely made up of quaver-length* notes - e.g. Turkey in the straw, or the Arkansas Traveler [6.1]. Where there is a break in this you may find you change direction, with the strong beats being played on the 'up' instead of the 'down', or you can try running two notes on to the same bow to keep the pattern constant. Different players usually develop a liking for playing the strong beat notes on one direction of bowing, but every now and then you find a phrase which involves 'reversing'. It's not like 'flat-picking' a mandolin or guitar where you would always pick - in an 8-beat bar - the notes falling on beats 1,3,5, and 7 downwards and those on 2,4,6, and 8 upwards.

The Nashville shuffle is the Cajun-sound bow: a long and two shorts. See [6.2] for an example. In bluegrass it is often used rather faster than in Cajun, and not often for long bursts. In Cajun the long stroke usually cover two notes, and this is not always the case in bluegrass. The Nashville Shuffle is of course the standard fiddle-tune intro.

The Georgia bow is a rather subtler version of the Nashville shuffle. It's also more difficult, as you have to make a one-quaver down-bow somehow equal to a three-quaver up-bow: i.e. you play one beat going downwards with the same length of bow that, playing upwards, you use for three beats. The effect is to give the down-bow a lot of extra 'wellie', and to make it even more difficult and exciting, it (the down bow) is on the off-beat - the second and fourth crotchets of the bar, or when the guitarist is on his 'strum' and the mandolin and banjo are doing their 'off-beat' business. You can of course reverse it so that the up-bow is short and the down-bow long. See [6.3] for a version of 'the Mississippi Sawyer', starting with the Nashville shuffle and then easing into the Georgia. The overall effect is much smoother, but with the real drive that characterises bluegrass music. Another good use of the Georgia bow is in Bill Monroe's 'Wheel Hoss'.

Not quite, but nearly unique to bluegrass is that shuffle you hear when a bluegrass fiddler gets into the Orange Blossom Special. I believe I mentioned before that the fiddler in a band often likes to throw back some of the syncopated 'rolls' at the banjo player, and this is your supreme chance to do so, as it involves just the same pattern of'3's and '2's spilling over the bar ends and generally playing havoc with the rhythms of the piece. It's combined with double-stopping - see [6.4] - to make a truly thrilling bit of fiddle playing to do or to listen to It's no accident that Orange Blossom Special is still one of the most popular tunes a bluegrass fiddler can play. There are of course other uses for this bowing style - see [6.5] - [6.7]. Another classic use is in the second part of 'Rawhide', where the fiddle player can try to steal the focus from the mandolin.

Each of these bowing techniques can give a particular rhythmic 'frisson' to the music you're playing. However, the more you play, the more you will ease into your own way of using the bow. Many players run several notes into one bow stroke, keeping the sound smooth, for most of the time, bringing in the special effects for what they can add at any particular part. I found when I was trying to play longer bows, I had paradoxically to concentrate on my left hand accuracy: when you are playing a plucked instrument or using the fiddle bow to set the start of each note, you have some latitude in just when you put your fingers down on the instrument neck, but if you are playing a long bow-stroke covering several notes, the evenness of each one is solely governed by how well you control your left hand fingers. [6.8] is a short example of how a piece might be bowed by one player on one occasion.

Crucial to all of the above bowing styles is relaxing the wrist and arm. This is not as easy as it sounds: when I was setting out to learn the fiddle I really felt I had enough to do already, what with finding out what notes to play where on which string, sorting out my left hand fingers, getting the notes in tune, keeping the bow hair the right distance from the bridge, and actually holding the fiddle itself in this strange (to a fretted instrument player) position under my chin. However, it probably has to come in the end, and if you find your arm hurting, or feel your playing is 'jerky' or 'scrapy' or that you're not getting out of the instrument the sound you feel is in it, I do suggest that you have a go at relaxing all the muscles in your arm except the ones which actually move the bow and hold it steady, and tensing those as little as you can. This will not only put you more in control and make bowing smoother, but it will also enable you to keep playing longer - better for those barn-dances!

*I'm using a standard bluegrass 'cut-time' quaver here. In more normal musical terms it's half the length of most people's quavers.

To buy books Bluegrass Fiddle check the Bluegrass Fiddle Collection at Sheet Music Plus.

You may also be interested in other Bluegrass Related Items on this site:

Playing Bluegrass

Bluegrass Harmony Singing - Tutorial Learning Bluegrass Jamming -Tutorial Learning to play the bluegrass instruments by Rick Townend Bluegrass Your Fiddle, Insiders guide and tutorial on Bluegrass Fiddling by Rick Townend A more complete definition of bluegrass and its background